Addressing Cognitive Biases in Emergency Pelvic and First-Trimester US

Peer learning and initial focus on imaging can help radiologists avoid errors

Cognitive biases are increasingly recognized as contributors to perceptual and interpretive errors in radiology, noted Melissa F. Tannenbaum, MD, former chief resident and PGY-5 radiology resident in the Department of Radiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston.

Now a breast imaging fellow at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Dr. Tannenbaum said that cognitive biases are a group of systematic errors that can occur due to the failure of mental shortcuts the brain relies upon to make quicker judgments.

She and her coauthors published a RadioGraphics article that explores how cognitive biases can contribute to diagnostic errors in emergency pelvic and first-trimester US.

“In the emergency department, we see many patients with acute pelvic pain that poses diagnostic challenges because the clinical presentation can be nonspecific,” Dr. Tannenbaum said. “We have noticed that cognitive biases in pelvic US interpretation can lead to many diagnostic errors.”

In their article, Dr. Tannenbaum and colleagues reviewed peer learning cases of nonpregnant and first-trimester pregnant patients who presented with acute pelvic pain in the emergency setting. Their goal was to highlight diagnostic errors and cognitive biases in interpretation with the hope of helping to mitigate such errors in the future.

A Closer Look at Biases

Dr. Tannenbaum and authors shared a case involving a tubo-ovarian abscess (TOA) mimic. “The lack of internal debris on US images and the lack of restricted diffusion on MR images favored cystic neoplasm over TOA,” the authors wrote.

And yet, the radiologist misdiagnosed ovarian cystadenofibroma as a TOA, mislead in part by information on the patient’s clinical history that revealed the presence of a fever. “In this case, the patient’s fever was due to methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia of an unclear source and was unrelated to the ovarian mass,” the authors noted.

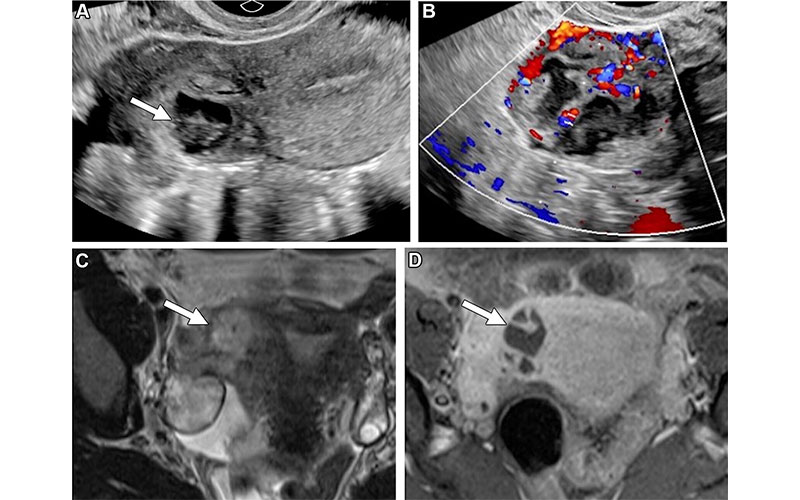

Missed TOA in a 32-year-old woman with right lower quadrant pain. (A) Sagittal transvaginal US image of the right adnexa shows a heterogeneous thick-walled structure with internal anechoic and hypoechoic components (arrow). (B) Color Doppler US image shows internal vascularity. The structure appears inseparable from the uterus and was noted on the radiology report as “likely representing a degenerating exophytic subserosal fibroid.” (C) Subsequent axial T2-weighted MR image shows a right adnexal heterogeneous hyperintense lesion (arrow). (D) Axial fat-suppressed postcontrast T1-weighted MR image shows predominately central nonenhancement within the lesion with thick internal septa (arrow). Findings are most concerning for a right adnexal TOA. Based on the size of the lesion, the patient was given antibiotics. Her mild leukocytosis, which was discovered after imaging, improved.

https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.240101 ©RSNA 2025

The case underscores how confirmation bias can cause radiologists to favor a diagnosis that aligns with initial clinical impressions rather than objectively evaluating imaging findings. “Examining the imaging study before reviewing the patient’s clinical history could have helped the radiologist avoid cognitive bias and would have allowed for a broader differential diagnosis,” the authors explained.

A similar influence of bias was demonstrated in a case where the provided history of a ruptured hemorrhagic cyst influenced US interpretation, leading to a missed ectopic pregnancy.

“If this history was not provided, the suspicion for ectopic pregnancy likely would have been higher, given the classic sonographic finding,” Dr. Tannenbaum said, adding that a left tubal ectopic pregnancy with rupture was confirmed at surgery.

The impact of cognitive biases extends beyond common diagnostic errors to more complex cases involving rare conditions. An example the authors provide is the misdiagnosis of an appendiceal mucinous neoplasm, a condition that results from an obstruction of the appendiceal lumen causing mucus to accumulate, which can be caused by benign or malignant lesions.

Dr. Tannenbaum and her colleagues linked the misdiagnosis to zebra retreat bias—meaning a tendency not to make a rare diagnosis because of a lack of confidence, despite the diagnosis being supported by evidence.

“Although an onion skin appearance was seen on the initial US image, which is pathognomonic for an appendiceal mucinous neoplasm, this diagnosis was not proposed, possibly due to unfamiliarity with the sonographic imaging features of this entity or self-consciousness in suggesting this rare diagnosis at US,” Dr. Tannenbaum said.

“Cognitive biases, such as confirmation bias highlighted in our study, are contributors to errors in radiology, and understanding these biases is important to help avoid these errors in the future.”

– Melissa F. Tannenbaum, MD

Peer Learning Helps Mitigate Bias

While clinical history can contribute to the development of cognitive bias, it cannot be overlooked. According to Dr. Tannenbaum, the optimal scenario is to leverage clinical history while improving knowledge about specific imaging features. Peer learning can help radiologists increase the diagnostic expertise needed to find this balance.

Peer learning is a beneficial tool for issuing and receiving feedback in a constructive, nonpunitive manner. It enables radiologists to learn from one another to improve the quality of care, Dr. Tannenbaum asserted.

“Over time, there has been a transition from traditionally used peer review to peer learning to foster a more collaborative culture around addressing and learning from errors in radiology,” she said.

“Peer learning helps to identify errors that may have high potential for repetitive occurrence and adverse outcomes,” Dr. Tannenbaum continued. “Cognitive biases, such as confirmation bias highlighted in our study, are contributors to errors in radiology, and understanding these biases is important to help avoid these errors in the future.”

Peer learning can also help radiologists become more familiar with common and uncommon causes of pelvic pain in nonpregnant and first-trimester patients, thus helping them avoid misdiagnoses and delayed diagnoses.

Finally, Dr. Tannenbaum said that familiarity with causes of pelvic pain in nonpregnant and first trimester pregnant patients in the emergency setting—with the understanding of how cognitive biases impact interpretation—is crucial for rapid and precise diagnosis.

“Through active participation in peer learning, radiologists may be able to devise strategies to prevent diagnostic errors in the future,” she concluded.

For More Information

Access the RadioGraphics article, “Lessons Learned in Emergency Pelvic and First-Trimester US: Focus on Cognitive Biases.”

Read previous RSNA News articles on mitigating errors in radiology:

- Top 10 Most-Feared Diagnostic Errors for Trainees in Pediatric Neuroradiology Emergencies

- Human Factors Drive Radiology Error Rates