Brain Abnormalities Seen in Military Members with Blast Exposure

Study challenges the idea that “invisible” injuries are harmless

In military service members with a history of repetitive blast exposure, researchers found that higher blast exposure correlated with changes in the functional connectivity between brain regions, according to a study published in Radiology. Even when standard MRI exams appeared normal, the researchers found clear abnormalities using more advanced MRI techniques.

“We found that service members with more blast exposure had more severe symptoms—including memory problems, emotional difficulties and signs of post-traumatic stress disorder—and that their brains showed weaker connectivity in key areas,” said lead author Andrea Diociasi, MD, neuroradiologist and past research fellow in the Department of Radiology at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School in Boston. “In short, repeated trauma seems to weaken the brain’s internal communication.”

Traumatic brain injury has diverse negative consequences for military personnel, affecting both the brain's structure and function. These effects are especially alarming for Special Operations Forces members who often face multiple blast injuries. Understanding the long-term neuroimaging implications of repeated blast injuries is challenging due to the variability of injuries in intensity, force and recurrence, underscoring the multiscale neurological implications of repeated trauma.

The research team analyzed structural and resting-state functional MRI data of Special Operations Forces members and the relationship between the frequency of blast injuries, persistent clinical symptoms and related changes to volume measurements in the cerebral cortex, as well as functional connectivity changes.

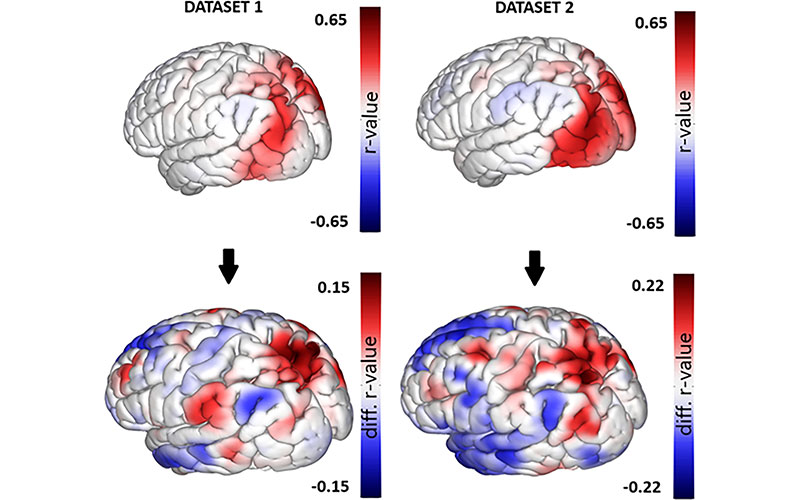

Upper panel displays functional MRI (fMRI) maps obtained from the functional connectivity multivariate patterns analysis conducted on dataset 1 and dataset 2. In particular, the average connectivity across all participants is illustrated with one of the clusters that showed differences between the groups. The colors depict the r value ranging from red to blue. Images in bottom panel highlight the differences between groups (color coded from red to blue), focusing on the same cluster chosen as a seed in the top row. The average connectivity is illustrated with the contrasted cluster across participants, showing a comparable disparity between the two datasets.

https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.233264 © RSNA 2025

Rethinking ‘Mild’ Brain Injuries

Included in the study were 212 service members with a history of repetitive blast exposure who underwent psychodiagnostics and a comprehensive neuroimaging evaluation. The group of service members were split into two datasets for model development and validation, and each dataset was divided into high and low exposure groups based on participants’ exposure to various explosives. An external age and gender-matched healthy control group of 212 participants was included in the volumetric analysis.

“We looked at over 200 Special Operations Forces members who had been exposed to blasts. Even though their brains looked normal on traditional exams, we used advanced MRI to find that the ones with more blast exposure had noticeable differences in brain activity and brain structure,” Dr. Diociasi said.

The service members also reported more symptoms such as anxiety, mood swings, irritability, poor concentration, forgetfulness, slowed thinking, headaches, nausea, fatigue, dizziness and balance problems, Dr. Diociasi noted.

“These symptoms were significantly more common in individuals with higher blast exposure and were linked to measurable changes in brain connectivity on advanced imaging,” he said. “The more blasts someone had experienced, the more these symptoms tended to show up—and the more their brain function seemed affected.”

Dr. Diociasi said that across very different populations, the same pattern emerges: mild but repetitive trauma can have lasting effects.

“We’re validating and expanding on prior work using a much larger and very specific population—Special Operations Forces—while also showing that these issues likely extend beyond the military,” he said. “The broader implication is that we need to rethink how we view ‘mild’ brain injuries, not just in soldiers, but across society.”

The study challenges the idea that “invisible” injuries are harmless. Dr. Diociasi notes that many people experience multiple head impacts in their lives—whether through military service, sports, accidents or other sources. The findings show that even if these injuries don’t cause obvious damage on a standard imaging exam, they can still change how the brain functions.

“We also noticed certain brain regions were actually larger in more-exposed individuals, which could reflect long-term tissue changes like scarring,” he said. “These aren’t injuries you can always see with the naked eye, but they are real—and now we can start measuring them.”

“The findings reveal that even when the brain looks ‘normal,’ it might still be carrying hidden signs of trauma—and we now have tools to detect them,” Dr. Diociasi said. “That opens the door for earlier detection, better treatment, and a deeper understanding of how repeated trauma affects the brain over time.”

Dr. Diociasi said that with their multimodal approach, the researchers tried to connect the dots. “But even now, many are still missing—filling in those gaps is the challenge ahead,” he said.

For More Information

Access the Radiology study, “Distinct Functional MRI Connectivity Patterns and Cortical Volume Variations Associated with Repetitive Blast Exposure in Special Operations Forces Members.”

Read previous RSNA News stories about brain imaging:

- Deep Learning Model Analyzes Head CT to Predict sTBI Patient Outcomes

- Radiology Could Play a Bigger Role in the Early Diagnosis of Alzheimer’s Disease

- MRI-Based Deep Learning Predicts Markers of Alzheimer’s Disease