Pediatric Head and Neck Disease Awareness Essential for Accurate Diagnosis

Not just little adults

In concert with the RadioGraphics monograph, RSNA News shares the latest in head and neck imaging.

“The causes and frequency of disease processes encountered in pediatric patients commonly differ compared to those encountered in adult patients,” said Alexandra M. Foust, DO, assistant professor of pediatric radiology at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, TN. “For example, a centrally necrotic cervical lymph node in a pediatric patient is most likely infectious—suppurative lymphadenitis—while in adult patients a necrotic cervical lymph node is much more likely to represent a nodal metastasis from an underlying carcinoma.”

Although there is some overlap with adult diseases, congenital lesions and developmental variants are much more common in the pediatric population and incidences of numerous infections and neoplasms differ.

In addition, compared with adults, differences in the appearance because of developing head and neck structures can further complicate interpretation in children. For example, certain anatomical landmarks are less pronounced or positioned differently. A radiologist must understand these differences to accurately interpret imaging studies.

Finally, young and/or developmentally delayed patients may be unable to communicate clinical symptoms, which can make it difficult to elicit accurate clinical histories. Thus, radiologists need to be aware of how pediatric head and neck diseases differ from adult diseases in presentation, imaging appearance and etiology.

In their RadioGraphics review, Dr. Foust and her team discussed the importance of using patient age and a location-based approach, as well as knowing the mimics, pearls and pitfalls for pediatric non-traumatic head and neck emergency imaging.

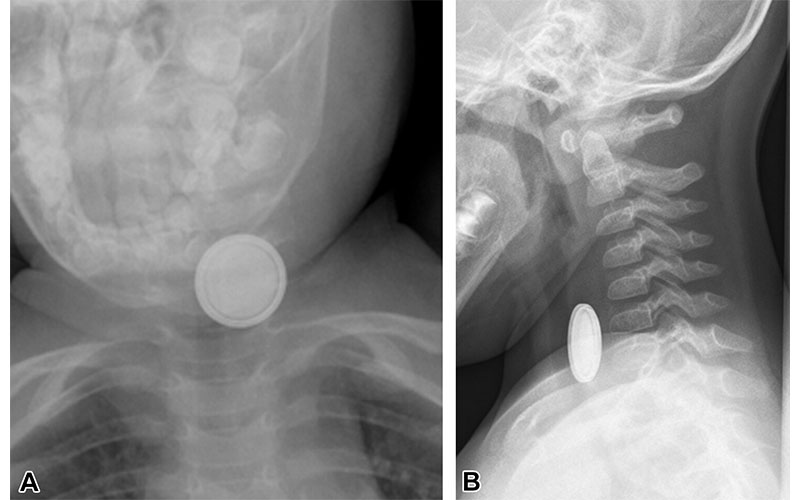

Recently ingested button battery in a pediatric patient. (A) Anteroposterior neck radiograph shows a double-ring appearance of the ingested button battery. (B) Lateral radiograph shows a beveled-edge appearance of the button battery. The location of the battery in the upper esophagus can be inferred by the round appearance of the battery in the anteroposterior projection and by the air-filled trachea observed to the right and in front of the foreign body. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.240027 © RSNA 2024

Common Presentations of Pediatric Head and Neck Diseases

Many families visit the emergency department (ED) for acute head and neck diseases, particularly infections. Because of the differences in anatomy and relative incidence of various diseases in children compared to adults, radiology trainees must be familiar with pediatric-specific considerations to guide timely and optimal management.

Common diseases that cause patients to present to the ED include suppurative lymphadenitis, coalescent otomastoiditis, and complications within congenital cystic lesions.

Suppurative lymphadenitis is an acute bacterial infection of the cervical lymph nodes, most commonly from Staphylococcus aureus or Streptococcus species. With nodal rupture, infectious collections can seed the deep spaces of the neck resulting in abscesses (e.g., retropharyngeal abscess) necessitating surgical drainage. As Dr. Foust and her team describe, US can aid in differentiating phlegmon from intranodal abscess, though contrast-enhanced CT may be needed for troubleshooting or evaluating anatomically extensive collections.

Coalescent otomastoiditis is also more commonly seen in pediatric patients. Clinical signs and symptoms include ear pain, postauricular tenderness and swelling. Imaging is typically reserved for patients who have toxic appearance and demonstrate symptoms concerning for complication, or have persistent symptoms despite antibiotic therapy.

“Important complications to be aware of include venous sinus thrombosis and epidural abscess,” Dr. Foust said.

Contrast-enhanced MRI is helpful for differentiating epidural abscess from a clot in the adjacent sigmoid sinus. In the case of epidural abscess, epidural fluid signal can be seen uplifting the adjacent opacified dural venous sinus.

“Pediatric patients are much less likely to develop Bezold abscesses along the sternocleidomastoid muscle than adult patients because their mastoid processes are not yet fully pneumatized,” Dr. Foust said.

Radiology residents working in the ED may also encounter various acute complications related to pediatric presentations of congenital cystic lesions (vascular anomalies, thyroglossal duct cysts, branchial apparatus anomalies).

“Presenting complications can relate to intralesional hemorrhage (lymphatic malformation), thrombosis (venous malformation), or infection,” Dr. Foust said. “Most of these are identified and treated during childhood and thus don’t present often in adult patients.”

US and CT play complementary roles in the ED to determine the location and anatomic extent of lesions as well as to assess for findings of acute inflammation, while MRI can be helpful for further lesion characterization after subsidence of acute inflammation.

Modality Selection And Working With Pediatric Patients

Modality selection is always a balancing act for pediatric patients.

“Radiologists use US as an initial study of choice more frequently in pediatric patients than in adult patients,” Dr. Foust said. “Pediatric patients are smaller, and thus the sonographic beam can better penetrate than in adult patients.”

Additionally, pediatric patients are much more sensitive to radiation compared to adult patients undergoing the same diagnostic study. Radiologists minimize radiation use where they can, which is another reason US is often a first-line imaging tool followed by consideration of MRI more frequently.

“The important trade-off with MRI, particularly in young patients who cannot hold still, is sedation may be needed since MRI is a longer examination than a neck CT,” Dr. Foust said. “There is no one size fits all solution and ultimately you consider all of these factors when choosing the best study for the patient.”

For pediatric patients with developmental delays that might prevent an accurate and timely diagnosis, it is important to be aware that they may be incapable of communicating clinical symptoms.

“In this situation, the patient cannot tell you what is going on. This may require more liberal use of diagnostic imaging studies to arrive at a timely diagnosis,” Dr. Foust said.

“Knowledge of pediatric presentations of acute head and neck diseases is critical for radiologists to provide timely and accurate diagnosis and to effectively collaborate with other health care professionals to provide valuable input into the overall care plan,” Dr. Foust concluded.

For More Information

Access the RadioGraphics article, “Nontraumatic Pediatric Head and Neck Emergencies: Resource for On-Call Radiologists.”

Read previous RSNA News stories on head and neck imaging:

- Somatostatin Receptor PET/MRI Useful For Imaging Head And Neck Cancers

- Imaging-Based AI Platform Predicts Head and Neck Cancer Spread

- Molecular Markers Star in Latest Guidance for Head and Neck Tumors