Radiologists at the Frontline of Preventing Elder Abuse

Abuse typically identified through imaging of key injuries

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that, globally, one in every six individuals 60 years or older is a victim of elder abuse. In the U.S., the prevalence of elder abuse is estimated at 10%, with higher rates happening among those who live in long-term care facilities.

“Contributing to the problem is that most cases go unrecognized,” says Mohamed Badawy, MD, radiologist and research assistant in the Computational Research Laboratory at University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston. “In fact, only one in every 24 to 27 elder abuse cases gets reported in the U.S.”

Elder abuse is also a problem that is on the rise. Increased longevity has played a role over the past few decades, but more recently the pandemic lockdown resulted in isolation and lack of community resources for many elderly people. This resulting loss of resources and community often corresponded with an uptick in abuse.

“This makes it all the more critical for physicians—including radiologists—to recognize the signs of abuse and neglect and take appropriate action,” Dr. Badawy added. He served as the lead author of a RadioGraphics review on the topic of nonaccidental injury in the elderly.

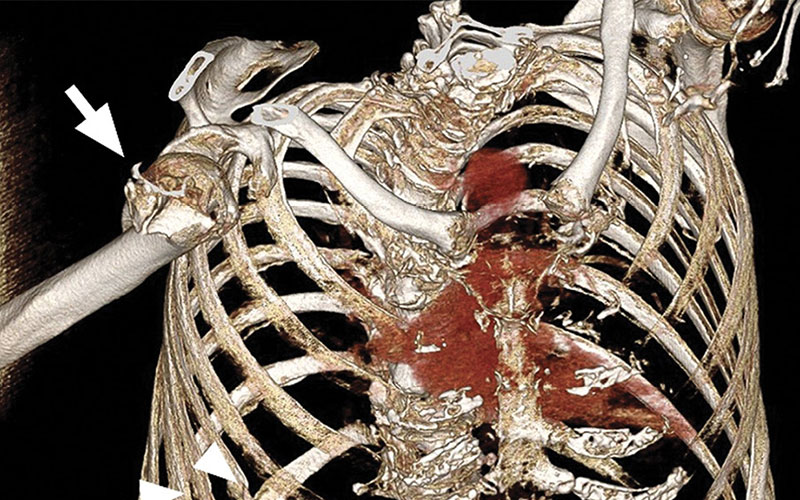

Elder abuse with anterior shoulder dislocation and multiple rib fractures in a 72-year-old woman who presented to the ED with right shoulder pain after a reported fall. Oblique osseous 3D reconstruction of the chest shows anterior dislocation of the humeral head associated with a comminuted impacted humeral head and neck fracture (arrow). Multiple age-indeterminate rib fractures (arrowheads) are also present.

https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.220017 ©RSNA 2022

Recognizing the Red Flags of Abuse

Whereas imaging has long played a role in identifying and preventing child abuse, that hasn’t been the case for elder abuse. Although this can be attributed to a lack of awareness of the issue, it is also the result of abuse being more difficult to identify in the elderly population.

“Comorbidities, osteoporosis, medication and being more prone to falling are factors that come with aging,” Dr. Badawy remarked. “This can make it more difficult for radiologists to distinguish between a standard injury and abuse.”

There are several “red flags” that could be indicative of abuse, according to Dr. Badawy and his research team.

Fractures that tend to be seen more frequently in cases of elder abuse include long bone fractures, facial fractures, posterior rib fractures and the presence of multiple fractures at various stages of healing. In a meta-analysis of 839 injuries in 1,247 abused elders from six countries, injuries to the upper extremities were the most common (44%), followed by fractures of the maxillofacial bones (23%) and lower extremities (11%).

“Because maxillofacial bones tend to be very strong, fractures to the face are unlikely to occur accidentally, such as from a fall,” Dr. Badawy said. “Likewise, spiral fractures, which are long bone fractures resulting from a rotational or twisting force, should raise suspicion of abuse, particularly if no history of trauma is reported.”

Distal ulnar fractures are also observed more frequently in cases of abuse than in non-abuse cases.

“While a fall on an outstretched hand is commonly seen in the emergency department and usually co-occurs with a fracture of the distal radial metaphysis, a fracture of the distal ulnar diaphysis may be associated with a victim raising their forearm in self-defense,” Dr. Badawy explained.

High-energy impact fractures can also be a red flag for elder abuse, especially those involving the upper ribs and shoulder girdle. As to the former, a posterior rib fracture has a low probability of being caused by an accident and instead tends to be the result of punches and kicks to a victim’s back. As to the latter, approximately 9% of all shoulder dislocations result from direct blows to the shoulder.

“These areas are generally too strong to fracture from a ground level fall, meaning any fracture to these areas should raise suspicion of abuse,” Dr. Badawy noted.

Hematomas, especially to the small bowel and soft tissue of the neck, buttock and inner arms, and severe decubitus ulcers are also common signs of abuse.

Reporting Often Starts With Imaging

Following imaging and suspicion of abuse, radiologists need to take their concerns to the referring physician. They can provide additional context, such as the functional status of the patient or history of injuries. Based on this, the case can be reported to the elder service provider, who can add information on known risk factors, such as poor physical health, mental illness, poverty and living situation.

“A red flag does not automatically mean elder abuse, which is why it is important to seek more information about the injury,” Dr. Badawy said.

When elder abuse is confirmed, medical providers should screen for acute medical conditions, including infection, bleeding and psychological distress, which may require prompt management and complicate inflicted injuries. Some patients may require hospitalization for extended observation and treatment. If there is concern for continued abuse, social workers, hospital administration and legal departments can get involved to separate victims from their caregivers and, if necessary, facilitate guardianship transfer.

While taking a multidisciplinary team approach to elder abuse is non-negotiable, the reporting often starts with imaging, according to Dr. Badawy.

“This is why we must continue to increase radiologists’ awareness of elder abuse and provide training on recognizing the red flags,” he concluded. “By knowing the warning signs, radiologists can start the early detection and reporting process, which is key to managing and preventing this growing problem.”

For More Information

Access the RadioGraphics study, "Nonaccidental Injury in the Elderly: What Radiologists Need to Know."

Access the Nonaccidental Injury in the Elderly infographic.

Read previous RSNA Newsstories on radiology's role in detecting violence:

Signs of Potential Elder Abuse on Imaging

Osseous injury and fracture

• Long bone fractures: spiral fracture, distal ulnar fracture

• High-energy impact injuries: first through fifth rib fracture, shoulder girdle injuries

• Posterior rib fractures

• Facial fractures: maxillofacial injuries, orbital fracture, mandibular fracture

• Multiple fractures and various stages of healing

Dislocation

• Anterior sternoclavicular joint

• Anterior shoulder dislocation, especially if recurrent, bilateral, and with no consistent history

Hematoma

• Intramural small-bowel wall hematoma

• Multiple subdural hematomas at different times and with skull fractures

• Large soft-tissue hematoma (>5 cm) or in unusual locations (e.g., neck, head, buttocks, soles or torso)

Other

• Extensive decubitus ulcers

• Multiple decubitus ulcers in unusual locations (e.g., shins or anterior chest wall)