Radiologists Should Stay Vigilant for These “Top 10” Complications after Liver Transplant

Imaging can ensure the health and life of the graft and graft recipient

As the indications for liver transplant expand, and as more patients are receiving liver allografts and enjoying increased survival, radiologists must be ready to spot critical hepatic graft complications in their daily practice—starting with a rundown of the diagnoses not to be missed.

To avoid pitfalls in image interpretation, radiologists should familiarize themselves with the surgical approaches to transplantation and with the specific technique used to create the surgical anastomosis, according to Claire E. Brookmeyer, MD, instructor of radiology at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine in Baltimore, MD. Such techniques can vary substantially from patient to patient.

These approaches were outlined by Dr. Brookmeyer and colleagues in a RadioGraphics article that also included insights on the scoring models for liver transplantation, an overview of imaging techniques, a summary of normal postoperative findings and a deep dive into the “top 10” complications.

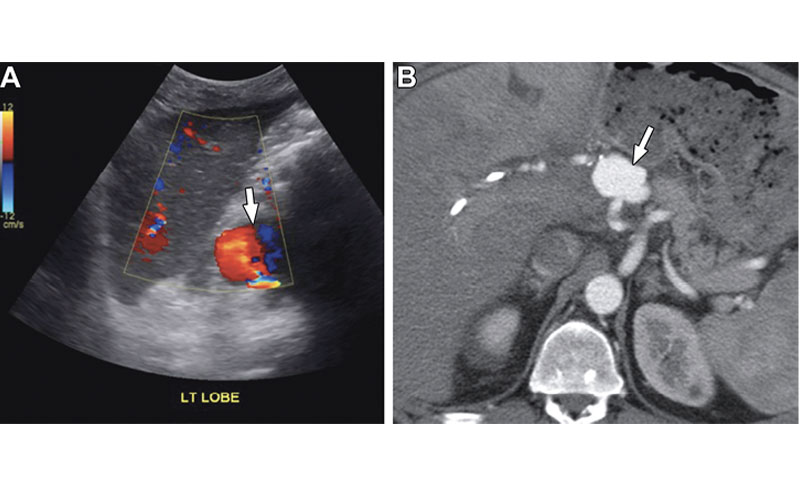

Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm in a 54-year-old man with abdominal pain and elevated liver function test results 1 year after liver transplant. (A) Color Doppler US image shows a round vascular lesion (arrow) with yin-yang flow, consistent with a pseudoaneurysm. (B) CT angiography findings confirm a pseudoaneurysm (arrow) in the extrahepatic segment of the hepatic artery.

Brookmeyer et al, RadioGraphics 2022; 42:702–721 ©RSNA 2022

1. Hepatic artery thrombosis

Postoperative hepatic arterial thrombosis, when it happens early, can lead to catastrophic outcomes such as biliary necrosis and infection. Delayed hepatic artery thrombosis and stenosis have variable outcomes, Dr. Brookmeyer said, but they could result in recurrent liver abscesses, bilomas or ischemic biliary structures. Thrombosis is diagnosed when US demonstrates an absence of Doppler flow in the hepatic artery and intrahepatic branches. When a radiologist identifies signs of impending thrombosis, such as low-velocity high-resistance flow, it should prompt urgent evaluation with contrast-enhanced US or CT angiography.

2. Hepatic artery stenosis

While it shares some clinical manifestations with delayed thrombosis, hepatic artery stenosis may respond to endovascular therapy, so it’s vital to use imaging to differentiate the two. If an abnormal waveform is recorded at US—including parvus tardus and a resistive index lower than 0.5—the radiologist should attempt to directly visualize the more proximal hepatic and celiac arteries. Follow-up is often necessary, Dr. Brookmeyer said, with short interval US, contrast-enhanced US or CT angiography. “Remember that the hepatic artery resistive index can be transiently elevated in the early postoperative period and should normalize within four days,” she advised.

3. Celiac artery stenosis

Dr. Brookmeyer stressed that it’s crucial for radiologists to recognize celiac artery stenosis on pretransplant images so that it can be treated before or during the transplant. Celiac artery stenosis may be asymptomatic before transplant because of the rich collateralization from the superior mesenteric artery. But after transplant, the collateral circulation is severed, and the graft becomes entirely dependent on the flow through the celiac axis and hepatic artery—and a preexisting stenosis may be unmasked.

4. Splenic artery steal

Also called nonocclusive hepatic artery hypoperfusion, splenic artery steal syndrome tends to occur within two months after transplant. Catheter angiography may demonstrate reduced blood flow to the hepatic artery and preferential flow to the splenic artery, gastroduodenal artery or left gastric artery. literature supporting it,” Dr. Brookmeyer said.

5. Hepatic artery pseudoaneurysm

These complications are rare but life threatening. Extrahepatic pseudoaneurysms are most often mycotic and they usually appear at the anastomosis or a site of prior angioplasty. Less common, intrahepatic pseudoaneurysms tend to occur at sites of prior biopsy or infection.

Aortohepatic conduit in a 52-year-old woman 1 year after a second liver transplant. Cinematic rendering of CT angiography shows an aortohepatic conduit (arrow), which is an alternative surgical technique for creating an arterial anastomosis. An aortohepatic jump graft was placed by using a donor iliac vein.

Brookmeyer et al, RadioGraphics 2022; 42:702–721 ©RSNA 2022

6. Portal vein inflow obstruction

Of the portal venous complications— which have an incidence of 1 to 2%— thrombosis is most likely, Dr. Brookmeyer observed. It appears as a filling defect in the portal vein on contrast-enhanced and color Doppler US images and on grayscale US it may be hyperechoic or anechoic. Radiologists should be on the lookout during the pretransplant evaluation for any large portosystemic shunts, especially those that extend beyond the transplant surgical bed, so that they can be addressed during surgery. After transplant, signs on Doppler US images are markedly decreased, bidirectional, hepatofugal or absent flow in the portal vein.

7. Hepatic vein outflow obstruction

Hepatic vein and inferior vena cava (IVC) complications are rare—with an incidence of 1%—and have three potential culprits. Hepatic vein and IVC stenoses, more common in pediatric and living donor transplants because of their more complex venous reconstruction, can present as monophasic hepatic venous waveform, reversal of the hepatic venous flow direction and, in severe cases, reversal of portal venous flow.

8. Biliary obstruction and leaks

Strictures are the most common cause of obstruction and they can be anastomotic or nonanastomotic. While the former tend to occur in the extrahepatic duct and aren’t associated with decreased survival, the less-common nonanastomotic strictures are more likely to occur at the hilum or multifocally within the intrahepatic ducts—and they can threaten the survival of the graft. When a radiologist spots biliary stones—which themselves can cause obstruction—they should investigate for underlying biliary strictures, Dr. Brookmeyer urged. Bile leaks are common in the early postoperative period, appearing in up to 20% of transplants, and they’re the second most common biliary complication after strictures.

9. Biliary cast syndrome

When it occurs, biliary cast syndrome can jeopardize the life of both the graft and the patient—with 17% requiring repeat transplant and a 12-month mortality rate of 30%. Early biliary cast syndrome can appear on US as isoechoic periportal branching structures. “Ultrasound cine clips from the porta hepatis to the liver periphery may be helpful in detecting subtle isoechoic biliary debris,” Dr. Brookmeyer said. The standard methods for diagnosing biliary cast syndrome are MR cholangiopancreatography, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography and percutaneous cholangiography. These will depict multifocal filling defects that involve the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts.

10. Neoplasm

“Liver allograft recipients are at increased risk for malignancy, owing to the immunosuppressive therapy they undergo and to preexisting conditions, such as viral hepatitis or alcohol use, that precipitate end-stage liver disease,” Dr. Brookmeyer said. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders can show up as hypoattenuating intrahepatic masses that mimic abscesses, or as an infiltrative or rounded mass at the porta hepatis. Liver transplant is offered in some cases of hepatocellular carcinoma or cholangiocarcinoma, so it’s important for radiologists to know what brought the patient for transplant in the first place. Any new mass in patients with these cancers should raise suspicion for metastatic or recurring disease, advised Dr. Brookmeyer.

When radiologists evaluate patients who are candidates for liver transplant, they should keep these “top 10” complication types in mind, according to Dr. Brookmeyer. They should also take advantage of the electronic health record and gather as much additional clinical information as they can, to supply context that can be critical to discovering a tricky diagnosis.

“If the imaging findings and liver function tests are discordant, further investigations may be necessary, particularly if there is deterioration in the liver function tests,” Dr. Brookmeyer said.

For More Information

Access the RadioGraphics article “Multimodality Imaging after Liver Transplant: Top 10 Important Complications,” as well as the invited commentary, “Imaging of Complications in Liver Transplant — What Every Radiologist Should Know."

This review is available for CME in the RSNA Online Learning Center at RSNA.org/Learning-Center.

Read previous RSNA News articles on gastrointestinal imaging: