MRI Technique Shows Promise for Measuring Abnormal Lung Function

Research reveals novel physiological biomarker in patients with asthma

Canadian researchers have developed a method for using 1H MRI to measure lung ventilation abnormalities in free-breathing patients.

The technique may be especially useful in small children and patients who are extremely ill and unable to hold their breath as needed during other, more commonly used imaging methods, said Dante Capaldi, PhD, lead author of the research published in the May issue of Radiology.

“Our research demonstrates that straightforward 1H MRI method at 3T can be used to measure abnormal specific ventilation,” said Dr. Capaldi, who was a PhD trainee on the team led by Grace Parraga, PhD, a scientist at Robarts Research Institute and a professor in the Department of Medical Biophysics at Western University, in London, Ontario, during his research. Dr. Capaldi is now a clinical resident at Stanford University.

Working with a team of researchers funded by the Canadian Respiratory Research Network and the Canadian Institutes of Health, Dr. Capaldi executed a proof-of-concept study using commercially- and clinically-available MRI pulse sequences to rapidly measure abnormalities in free-breathing patients.

The research concept was also acknowledged with a 2017 RSNA Trainee Research Prize for the project, “Measuring Specific Ventilation using Four-dimensional Magnetic Resonance Ventilation Imaging: A Novel Physiological Biomarker of Asthma.” “Our RSNA research focused on developing new pulmonary functional imaging biomarkers in patients with asthma and COPD using breath-hold hyperpolarized 3He and 129Xe MRI, which provided a foundation for this new work,” Dr. Capaldi said.

Dr. Capaldi hypothesized that in patients with poorly controlled severe asthma, MRI specific ventilation and gas distribution abnormalities would be highly correlated. They sought to use imaging to measure specific ventilation and to correlate it with previously developed and validated biomarkers.

A Team Brainstorming Approach

The researchers recruited 30 subjects between 18 and 85 years of age. Of the participants, 23 had asthma and seven were healthy volunteers. All subjects underwent free-breathing 1H MRI, static breath-hold hyperpolarized 3HE MRI, spirometry and plethysmography.

“We are highly engaged with our patients with severe asthma who traveled long distances to attend clinic and also attended our site for imaging,” Dr. Capaldi said.

Though the team easily acquired data and images, they took an outside-of-the-box approach to generating a pipeline for analysis by brainstorming for ideas with local collaborators and PhD students who had not previously thought about lung imaging. They used software to perform processing and statistical analysis of the data.

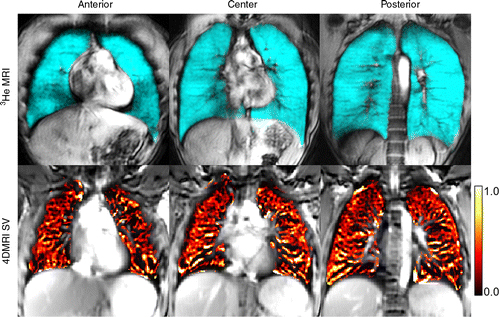

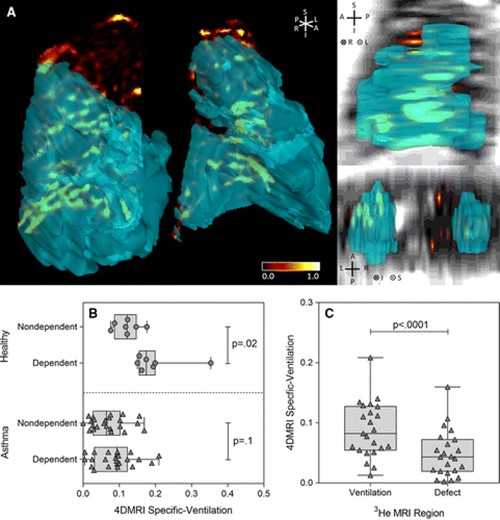

The results of the study revealed that both 1H MRI-derived specific ventilation and hyperpolarized 3HE MRI-derived ventilation were significantly greater in healthy volunteers than those in asthma patients. For all subjects, 1H MRI-derived specific ventilation correlated with plethysmography-derived specific ventilation and hyperpolarized 3H MRI-derived ventilation percentage.

Correlations were also made with forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity, ratio of residual volume to total lung capacity and airway resistance.

In patients with asthma, co-registered 1H MRI specific ventilation and hyperpolarized 3HE MRI maps showed that specific ventilation was diminished in corresponding 3HE MRI showing distribution abnormalities compared with well-ventilated regions.

The results are promising, according to Dr. Parraga, also an author on the study.

“The ventilation abnormalities captured during patient breath-hold clearly and spatially correlated with abnormal specific ventilation measured in asthma patients who were free breathing. From a translational point of view, this means that for patients, conventional MRI can be considered to help measure regional lung function in a physiologically-relevant manner,” she said.

“We showed the exact airways and parenchyma abnormalities from which the abnormal specific ventilation stemmed, and the measurement reflected the same abnormalities observed in patients using inhaled contrast agents in breath-hold,” Dr. Parraga added.

Following up their Radiology study, the researchers would like to test their approach in a larger, randomized, controlled treatment study in patients.

“We would like to better understand how and where specific ventilation changes occur after anti-inflammatory therapy in patients with COPD and asthma,” Dr. Parraga said.

Web Extras

- Access the Radiology study, “Free-breathing Pulmonary MR Imaging to Quantify Regional Ventilation,” at https://pubs.rsna.org/doi/figure/10.1148/radiol.2018171993