MRI Plays Increasingly Vital Role in Living Donor Liver Transplantation

Research shows potential of MRI vs. CT in transplant procedure

Advances in MRI have made the modality a powerful tool for imaging potential living liver donors, providing a “one-stop shop” that can, in many cases, significantly reduce or completely eliminate the need for pre-procedural CT, according to experts in the field.

Liver transplantation is the best hope for patients with end-stage liver disease and/or hapatocellular carcinoma. However, the number of livers available every year from deceased organ donors continues to fall well short of demand.

Lack of available organs pushed the development of living-donor liver transplantation, a procedure in which donors give portion of their liver to recipients. The procedure was first developed for pediatric patients in the 1980s and expanded into the adult population the following decade.

“The median wait time for a liver can be very long, and some patients may even die during the waiting time,” said Kartik S. Jhaveri, MD, director of abdominal MRI at the University Health Network, University of Toronto, Canada, which has one of the largest living-donor liver transplant programs in North America. “When a family member or someone close to the patient is willing to donate part of a liver, that certainly helps relieve the time pressure of waiting for a transplant.”

Living-donor liver transplantation takes advantage of regenerative powers that allow the liver to grow back to its original size in only a few weeks. In adults, surgeons replace the diseased liver with the right half of the donor’s liver, while pediatric patients receive a portion or the whole donor’s left lobe.

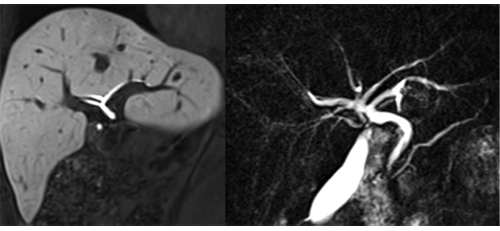

Thorough imaging evaluation of the donor liver is vital to ensure that a liver is suitable (in addition to clinical, biological and psychsocial evaluations). Imaging assessment focuses on three key areas in the donor liver: fat content, vascular system and biliary tree anatomy, which consists of the bile duct and the associated network of smaller ducts that carry fat-digesting bile from the liver to the digestive tract.

“Liver anatomy, volume, morphology, the hepatic artery, the portal and hepatic veins and biliary anatomy are all very important when considering donors, in addition to any important incidental finding (e.g., liver or renal tumor),” said Bachir Taouli, MD, director of body MRI at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York City. “The anatomy can be complex; you have to be very careful so that you minimize risk to the donor and avoid complications that may affect both the recipient and donor.”

MRI Offers Advantages Over CT

CT was the favored option for imaging donor livers through the first decade of the 21st century, while MRI was limited primarily to bile duct assessment due to its spatial resolution limitations. But advances in contrast agents and pulse sequences has expanded the role of MRI.

“MRI has progressed enormously in terms of image quality, acquisition speed and reporting,” said Dr. Taouli, who reported that his institution performs approximatley 20 living-donor transplants every year. “MRI has become almost the only way to examine living donors for liver transplantation.”

Using MRI, the potential donor is examined for bile duct anatomy, liver fat/iron and blood vessels in one scan. In the bile duct, where most of the post-transplant complications occur, it can help prevent or minimize biliary complications such as post-transplant leakages, infections and abnormal biliary drainage in donors.

“The anatomy of the bile duct greatly affects surgery,” Dr. Taouli said. “There are two different containers that drain bile: one on the left, one on the right. If the surgeon does not know where to cut and stitch the bile ducts, a patient could be left with a lobe that has no drainage, and if the liver cannot drain bile it will not function.”

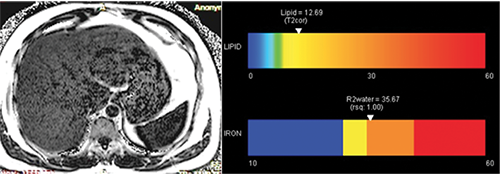

The amount of fat in the donor liver is also critical to a successful transplant, said Dr. Jhaveri, who published a 2017 review in the American Journal of Roentgenology demonstrating how MRI has rapidly evolved as a noninvasive alternative to invasive approaches to liver transplantation.

Research has shown that the presence of fat in a donated liver has a negative effect on the recipient after transplantation. By evaluating the liver for fat content, MRI techniques help reduce the need for a liver biopsy in donor candidates.

“The distribution of fat in the donor liver can be heterogeneous,” said Dr. Jhaveri, who has also contributed MRI-liver related research to Radiology and RadioGraphics. “MRI allows us to assess the entire liver for fat, as opposed to a biopsy that samples only a small area.”

MRI is Becoming “One-Stop Shop” for Liver Donor Imaging

CT still has advantages over contrast-enhanced MR angiography for assessing vascular anatomy, particularly in the smaller blood vessels, Dr. Jhaveri said. But MR angiography is closing the gap as the technology evolves.

All these advances point to a role for multi-sequence MRI as a “one-stop shop” for liver donors that could mitigate or even eliminate the need for CT, Dr. Jhaveri said. Potential donors could undergo MRI first and move on to CT only if more information is needed.

“We are already performing MRI to assess the biliary tract,” Dr. Jhaveri said. “Now, we can use it to assess arterial anatomy and liver fat, enabling patients to be comprehensively evaluated in one scan. This represents significant cost savings for healthcare and eliminates radiation exposure to the donors who are typically healthy individuals.”

Using this protocol, Dr. Jhaveri estimates that up to 30 to 40 percent of the living-donor patients at his hospital would not need a CT scan.

“MRI is already a standard approach,” he said. “We have been doing it for many years now. It is a constant process of evaluation, and with continued improvements in the technology, we may one day be able to switch completely to MRI.”