Do Babies Feel Pain Like Adults? MRI Research Offers New Insights

Babies experience some aspects of pain in a similar way that adults do, new MRI research suggests

Novel MRI research has determined that infants have patterns of pain-related brain activity similar to adults but with a much lower pain threshold. The study findings highlight the importance of developing effective pain management strategies for infants, researchers said.

Infants—particularly those born prematurely—are sometimes subjected to painful procedures, like line and tube placement and repetitive blood draws. A 2014 Neonatology study from the Netherlands found that each infant in the neonatal intensive care unit averaged more than 11 painful procedures per day. Compared with adults, less is known about how infants experience pain, which has led to a lack of recognition in clinical practice. MRI has been used to study pain-related brain activity in adults, but is difficult to perform on infants because it requires the subject to remain still during imaging.

For the new study, researchers from the Department of Paediatrics at the University of Oxford, U.K., were able to address this issue by enlisting the help of the babies’ parents. A report on the research appears in the April 21 online edition of the journal eLife.

“Until recently, researchers didn’t think it was possible to study pain in babies using MRI because, unlike adults, they don’t keep still in the scanner,” said study lead author Rebeccah Slater, Ph.D., associate professor of paediatric imaging at the University of Oxford. “However, as babies less than a week old are more docile than older babies, we found that their parents were able to get them to fall asleep inside a scanner so that we could study pain in the infant brain using MRI.”

The study compared 10 healthy infants between one and six days old and 10 healthy adults aged 23 to 36 years. In most cases one or both parents stayed with the babies and a trained medical professional was always present. Babies were cuddled and nursed to get them to fall asleep inside the MRI scanner. Researchers used a special bean bag to help keep the babies’ heads still and earphones to reduce the scanner sound.

The Oxford researchers used Blood Oxygenation Level Dependent (BOLD)-based MRI, a technique in which the signal changes in intensity depending on the oxygen level in the blood.

“Brain activity causes a local increase in blood flow, bringing with it oxygenated blood that causes the images to get a little brighter,” said Stuart Clare, Ph.D., university research lecturer at the University of Oxford. “This non-invasive method doesn't require any extra equipment—just a researcher with a stopwatch to provide the stimulus at the right time.”

To monitor head motion, researchers also used Prospective Acquisition CorrEction (PACE), a vendor-supplied technology that tracks the subject’s movement from scan to scan making minor adjustments to the imaging prescription to ensure that the region of interest is always in view.

“At first we thought that this technology would make a big difference in the study—but, provided the babies are settled in the scanner, which happened most of the time—it would be possible to do a study like this without it,” Dr. Clare said.

During scanning, subjects were poked on the bottom of their left foot with special retracting rods that can be applied at several different force settings. Each stimulus was administered 10 times for about one second each.

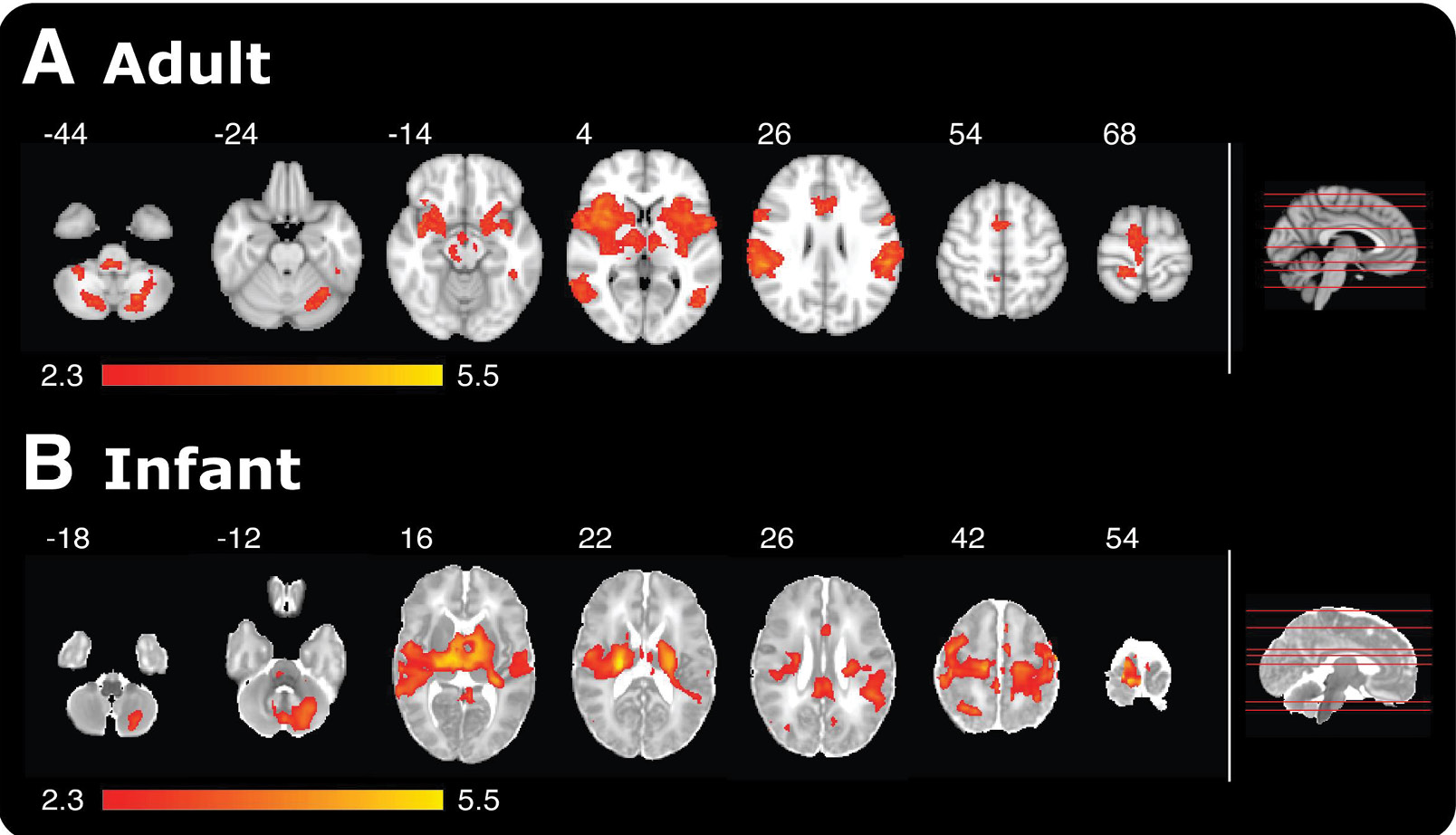

When researchers compared MRI scans from the babies with those of adults exposed to the same intensity stimulation, they found that 18 of the 20 brain regions active in adults experiencing pain were active in babies. Scans also showed that babies’ brains had the same response to a weak poke as the adults did to a stimulus four times as strong, suggesting that they may have a much lower pain threshold than adults.

“This is particularly important when it comes to pain: obviously babies can’t tell us about their experience of pain and it is difficult to infer pain from visual observations,” Dr. Slater said. “Historically it was thought that babies’ brains may not be developed enough for them to really ‘feel’ pain—that any reaction is just a reflex. Our study provides evidence that this is not the case.”

Reexamining Pain Prevention Strategies

The findings highlight the importance of pain prevention strategies in infants, researchers said. As recently as the 1980s it was common practice for babies to be given neuromuscular blocks without pain relief medication during surgery.

“Thousands of babies across the U.K. undergo painful procedures every day, but there are often no local pain management guidelines to help clinicians,” Dr. Slater said. “Our study suggests that not only may babies experience pain but they may be more sensitive to it than adults. If we provide pain relief for an older child undergoing a procedure, then we should look at giving pain relief to an infant undergoing a similar procedure.”

Rachel Edwards, one of the parents involved in the study, was motivated to participate after her first son Rhys was born four weeks early and had to go to a special unit where he received more than 10 heel lances a day without any pain medication. Wanting to know more about how babies feel pain, she gave permission for her newborn son Alex to take part in the study.

“Before Alex went in I got to feel all the things he would feel as part of the study including the pencil-like retracting rod,” she recalled. “It wasn’t particularly painful; it was more of a precise feeling of touch.”

There are numerous pain management strategies for infants, and not all carry the risks associated with powerful drugs. For instance, studies have shown that a small amount of a sweet, sucrose-based solution placed in the infant's mouth is a safe and effective strategy for management of short-term pain. Pain or stress-reducing strategies like those outlined in the Newborn Individualized Developmental Care and Assessment Program are also helping to raise awareness.

In the future, the Oxford researchers hope to identify a neurological pattern of pain-related brain activity in babies’ brains similar to that shown in adults in recent MRI studies.

“This could enable us to test different pain relief treatments and see what would be most effective for this vulnerable population who can’t speak for themselves,” Dr. Slater said.

“This intriguing study brings together developmental neuroscience and cutting-edge neuroimaging to advance our understanding of pain,” added Raliza Stoyanova, Ph.D., science portfolio advisor for Wellcome Trust, the London-based biomedical research charity that funded the research. “The finding that brain networks similar to those found in adults are activated in babies exposed to pain stimuli suggests that babies may feel pain in a similar way. We may need to re-think clinical guidelines for infants undergoing potentially painful procedures.”

Web Extras

- Access the study, “Development: How Do Babies Feel Pain”? at elifesciences.org/content/4/e07552.full